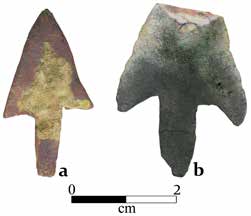

These sheet copper or brass arrow points were recovered from the Holy Ground site.

Credit: Center for Archaeological Studies, University of South Alabama

In the first half of the 19th century, Creek Indians in what is now Alabama watched with alarm as white settlers encroached on Creek lands. The Creeks were divided over how to cope with the intrusions of land hungry settlers, partly because the Creeks’ lives were so intertwined with those of the settlers and their African slaves due to intermarrying. It was inevitable that what started out as a civil war within the Creek nation would involve everyone on the southwestern frontier and forever change its cultural landscape. The Conservancy’s 400th site, Holy Ground Village and Battlefield, played a key role in these historic events.

Although they had spent years peacefully coexisting with the Euro-Americans and their slaves, not all Creeks accepted the U. S. policy of acculturation that promoted the planting of cash crops, the acquisition of private property, livestock, and slave ownership. Some factions within the Creek tribe opposed abandoning sacred traditions and believed that redistributing traditionally communal lands to individuals would lead to the loss of all Creek lands and their tribal identity. These people were urged by religious leaders called “prophets” to destroy things such as plows, looms, livestock, and all vestiges of white influence and to return to traditional ways. Tensions increased and the Creeks fractured into warring camps. The traditionalist camp became known as the Red Sticks, an allusion to the red wooden war club used by the Creeks.

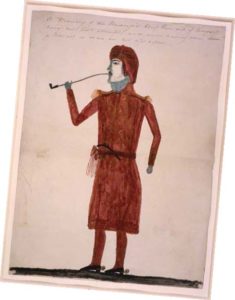

A self portrait of Josiah Francis wearing a British officer’s uniform. The portrait was drawn in England in 1816, where

Francis was living at the time. He later returned to the United States and was captured and executed by Gen. Andrew

Jackson in 1818. Copyright The Trustees of the British Museum.

In August of 1813, following their devastating attack on a stockade housing a militia and settlers, which became known as the Massacre at Fort Mims, Red Stick leader William Weatherford and his warriors regrouped at a village called Econochaca, or the Holy Ground. Located near the Alabama River and surrounded by swamps and ravines, Holy Ground had been established a few months earlier by a Red Stick prophet named Josiah Francis. Francis claimed to have erected an invisible barrier around the village that no white man could penetrate.

On December 23, 1813, the invisible barricade was penetrated by U.S. Infantry and Mississippi Territorial troops who were bent on avenging the deaths of their comrades at Fort Mims. Accompanying the troops were Chief Pushmataha and 150 Choctaw warriors. Knowing an attack was imminent, the Red Sticks had already moved their women and children across the river to safety. The Red Sticks were outnumbered and outgunned, but most managed to escape. Weatherford was one of the last to be seen on the battlefield, and legend has it that he and his horse leapt off the bluff and into the Alabama River to make their escape.

With financial assistance from a National Park Service grant, archaeologists Gregory A. Waselkov with the University of South Alabama and Craig Sheldon with Auburn University recently found the Holy Ground site near the confluence of House Creek and the Alabama River. Recovered artifacts and an 1818 land survey plat helped confirm the site’s location. What was once an Indian village of approximately 200 houses is now a residential development. Fortunately, most of the lots have not been sold and the owner is sympathetic to the site’s historic importance. The Conservancy plans to purchase seven lots to ensure the site’s preservation. As Waselkov points out, almost nothing is known about Red Stick material culture or the extent to which they avoided white influences. So far, quite a few nails have been found at the site. Archaeologists will compare Holy Ground to contemporaneous Creek villages not part of the Red Stick movement. According to Waselkov, official accounts of the battle are vague and future research at the site could shed light on that aspect as well.

Because so many significant archaeological sites in this region have been lost to mining or recreational and residential development, Waselkov and Sheldon were pleasantly surprised the Holy Ground site was still intact, and they are extremely pleased that the Conservancy has acted to ensure its survival. “It is hard to believe that Greg and I first started talking about finding Holy Ground only a few months ago,” Sheldon said. “We are so glad that this will come to a good end, having found so many sites only to see them destroyed.”