In August of 2015, The Archaeological Conservancy’s Board of Directors and staff met in Columbus, Ohio for their semi-annual business meeting. The next morning those without early flights home traveled about an hour south to Chillicothe, the center of the Hopewell Culture heartland 2000 years ago, and today, the home of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park.

The park began in 1921 when President Warren Harding, an Ohio native, used his powers under the Antiquity Act to declare a portion Camp Sherman, a decommissioned World War I training base, as Mound City National Monument. The mission of the National Monument was interpreting and celebrating the achievements of the Hopewell Culture. The Hopewell Culture is the name archaeologists give to the American Indian societies that brought about one of the great florescent periods in North American prehistory from about 50 BC to AD 450 in the American Midwest.

TAC board members and staff listen as NPS ranger expounds on Mound City. Photo Bliss Bruen/ The Archaeological Conservancy.

The Hopewell Culture is characterized by the construction of massive geometric earthworks, sometimes enclosing more than 100 acres with earthen walls miles long and by long-distance trade for unusual raw materials such as copper, mica, grizzly bear teeth, marine shell and obsidian. Materials from as far away as Idaho, and the Gulf Coast made their way to what is now central Ohio,where they were frequently fashioned into small objets d’art of remarkable craftsmanship. The area near the confluence of Paint Creek and the Scioto River – present-day Chillicothe – was the center of Hopewell activity and thus a fitting location for a national monument.

Copper bird recovered from Mound City. Long described as a falcon, the piece may represent an extinct Carolina parakeet. Photo NPS.

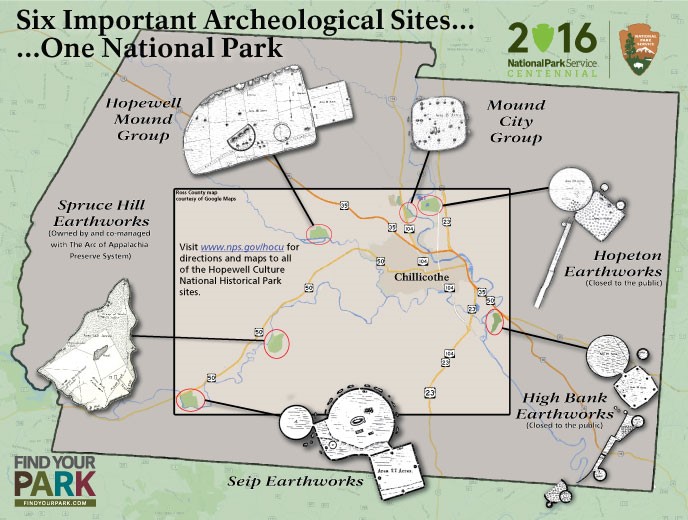

The Mound City archaeological site is a rectangular enclosure of about 13 acres encompassing at least 23 mounds. While an impressive site by almost any standard, it is hardly the largest or grandest Hopewell construction. It was chosen as the national monument because the Antiquity Act empowers the President to dedicate only federal lands as national monuments. Mound City was uniquely eligible because it had been incorporated into the U.S. Army base. After the restoration of the mounds and earthwork and the construction of a visitor’s center, Mound City served for about 60 years as the focus of the National Park Service’s interpretation of the Hopewell Culture.

TAC board members and staff walk by the 17-foot high central mound at Mound City. Photo Bliss Bruen/ The Archaeological Conservancy.

By the early 1980s, however, knowledge of the extent and importance of the Hopewell Culture had increased greatly, and it began to be recognized that more should be done to interpret it. Plans were made to expand Mound City National Monument to the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. Initial plans called for adding one additional site, the Hopeton Works, located across the Scioto River from Mound City.

TAC CEO Mark Michel recounts the saga of The Hopewell site’s preservation in front on an NPS interpretive sign at the site. Photo Bliss Bruen/The Archaeological Conservancy.

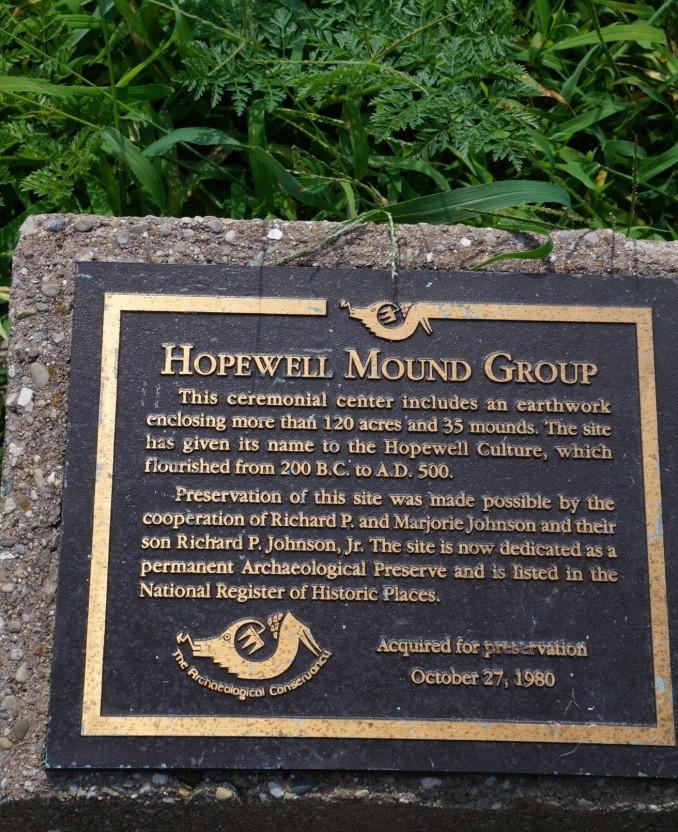

Given the great importance of the Hopewell Culture in the prehistory of the eastern United States, it is hardly surprising that the Chillicothe area became one of the first places that The Archaeological Conservancy began its work. Mark Michel, one of the co-founders of TAC and still its CEO, began to travel to Chillicothe to locate Hopewell sites on private land that might be worthy of permanent preservation. To his great surprise, he learned that the Hopewell site itself – the site so impressive that it had given its name to the entire cultural phenomenon – was not only still in private hands, but was actually slated for subdivision into parcels for residential development. Facing the imminent loss of one of the nation’s most noteworthy archaeological sites, TAC negotiated a purchase of the site for $80,000, a very significant portion of new organization’s budget. The Hopewell site thus became the second site preserved by The Archaeological Conservancy.

The Conservancy’s memorial plaque still present at the Hopewell site. Photo Bliss Bruen/ The Archaeological Conservancy.

Michel, who had a background in government, then began to work with the National Park Service to draft legislation that authorized them to acquire four additional Hopewell sites and to study another four for possible acquisition. The authorization bill, which created Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, was passed in the early 1980s, but actual acquisition of additional sites would be delayed for nearly two decades due to a lack of funding. By the end of the century, NPS would successfully acquire the Hopeton and Seip sites, as well as the Hopewell and High Bank sites, two sites pre-acquired by TAC and held for years awaiting purchase by the National Park Service. In 2007, NPS was able to undertake the management of the Spruce Hill Earthworks, another TAC pre-acquisition.

TAC’s visit to the park in August included trips to Mound City and the Hopewell site. Mound City remains the most visually striking of park’s holdings with reconstructed mounds up to 15 feet high and an enclosing wall three feet high. The small museum holds many striking examples of Hopewell craftsmanship, and the interpretation of the culture is well done. Sadly, the Hopewell site bears the marks of over 150 years of plowing, so its walls and mounds are generally difficult to discern. The parks trails and interpretive displays do much to make a visit to the place worthwhile, however.

Preservationists in foreground; urban sprawl in the background. If not for The Archaeological Conservancy, the Hopewell site would have been lost to residential development. Photo Bliss Bruen/ Archaeological Conservancy.

Learn more about Hopewell Culture and Plan a visit to Hopewell Culture National Historical Park .