By Paula Neely

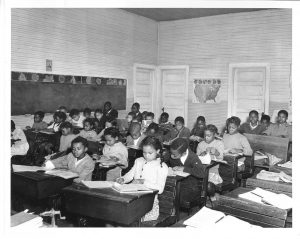

Third, fourth, and fifth graders attend class at Bethel Rosenwald School.

Photo credit: National Archives

Hiking through a shady hardwood forest on a sunny day in June, archaeologist Colleen Betti pointed out the spot where the Bethel Rosenwald School for African American students once stood. She motioned toward a long swath of daffodils that helped her mark where to begin looking for remains of the school. Betti said that daffodils along the front of the school were mentioned in descriptions from a prior excavation, before it was known to be a Rosenwald school. After the school closed in 1951, it eventually fell into disrepair and was demolished. Nothing of the structure remains above ground today, and no one knew exactly where it was located until Betti discovered three brick piers that matched up with construction plans for the building.

Several years ago, for her doctoral dissertation, she conducted excavations at the Bethel and Woodville Rosenwald schools—both built in 1923 in Gloucester County, Virginia—to learn more about the daily lives of the students set against the backdrop of the Jim Crow era, when state and local laws enforced racial segregation in the 19th and 20th centuries. “I’ve always felt like children were missing from archaeological stories,” she said, noting that the majority of the artifacts discovered at the school sites were used or touched by kids. Her excavations are also the first large-scale archaeological studies of Rosenwald schools.

Between 1912 and 1933, Julius Rosenwald, the son of Jewish immigrants and president of the Sears and Roebuck Company, in collaboration with Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute and advocate for African American education, helped create and fund about 5,000 schools in 15 southern states. Known as Rosenwald schools, they served nearly a third of Black students in the South. “They played a massive role in furthering education,” Betti said. A study conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago found that there was a significant gap in the education of Black people and white people prior to World War I, but the gap narrowed significantly between World War I and World War II. The study identified Rosenwald schools as the largest single factor driving the improvement with significant, quantifiable improvements in attendance, literacy, and test scores.

Before the emancipation of slaves, it was illegal for Black people to receive education. “After the Civil War, in 1869, Virginia’s Reconstruction constitution mandated that (all children) receive free education. It was the beginning of the public school system,” Betti said. Localities had until 1876 to comply.

This is an excerpt of Student Stories Emerge at Rosenwald Schools in American Archaeology, Fall 2024 | Vol. 28 No. 3. Subscribe to read the full text.

FURTHER RESEARCH

Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald Schools Special Resource Study (2024)

H.R.3250: Julius Rosenwald and the Rosenwald Schools Act of 2020

John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library, Fisk University

A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America, Andrew Feiler (2021)