By David Malakoff

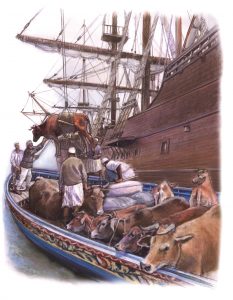

African cows were imported by West African traders to Spanish colonists in the 15th century. Illustration: Steve Patricia

Just north of the bustling main plaza of Antigua, an historic city in the Guatemalan highlands founded by Spanish colonists in the 1500s, archaeologists made a striking find at homes destroyed by an earthquake some 250 years ago: intricately tiled courtyards that feature the image of a fierce two-headed eagle as well as geometric designs. Also remarkable is that many of the tiles are made from the knucklebones of cows.

Indeed, the researchers calculated the courtyards hold nearly 9,000 bones taken from the lower legs of at least 2,200 animals. The tilework reflects not only the talents of the artisans who created it, but also the important role that cattle came to play in North American societies after Christopher Columbus first brought the animals to the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in 1493. Spanish colonists ultimately established cattle herds—often numbering 10,000 head or more—across New Spain, which encompassed Mexico, Central America, and much of the southern United States, setting the stage for their spread north and south.

Cattle made many wealthy, and in Antigua Guatemala, some affluent homeowners flaunted those riches by using thousands of carefully trimmed cow knucklebones to create intricately tiled courtyards, an architectural tradition borrowed from their Spanish homeland. Photo: Nicolas Delsol / Université Laval

Now, three recent research efforts have used a range of techniques—including painstaking analyses of thousands of cow bones recovered at digs and of ancient DNA and chemical isotopes stored within those bones—to provide new insight into the origins of America’s first cows, as well as how those exotic animals shaped both colonial and Indigenous communities. The findings, from Mexico, Haiti, Guatemala, South Carolina, and Arizona, reveal that “the arrival of cattle in America created a major cultural shock wave that had a tremendous impact on social structures, agriculture, and the economy,” said Nicolas Delsol, a zooarchaeologist at the Université Laval in Quebec. The animals transformed landscapes by trampling rangelands and riverbanks and consuming vast quantities of vegetation. They catalyzed the creation of industries previously unknown in North America, including large-scale butchering and leather tanning operations, and sparked demand for whole new classes of skilled labor, including vaqueros—horse-riding cowboys who knew how to wrangle the potentially dangerous animals. Free-ranging herds often sparked disputes between European colonists and Indigenous farmers—tensions that ultimately led to new laws and social institutions, and in some cases even unintentionally boosted the trans-Atlantic trade in enslaved people from Africa. “Cattle might be pretty unglamorous animals,” said archaeologist Martha Zierden, curator emeritus of The Charleston Museum in South Carolina. “But they played a big and often under-appreciated role in the evolution of colonial America.”

Archaeologist Nicolas Delsol analyses cattle bones in the Environmental Archaeology Lab at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Photo: Jeff Gage / Florida Museum of Natural History

This is an excerpt of When Cows Came to America , in American Archaeology, Spring 2024, Vol. 29, and No. 1. Subscribe to read the full text.

FURTHER READING

- Cattle in the Postcolumbian Americas: A Zooarchaeological Historical Study, Nicolas Delsol, University Press of Florida (2024)

- Emergence and Evolution of Carolina’s Colonial Cattle Economy, Martha A. Zierden et al., The Charleston Museum (2022).

- Rendering Economies: Native American Labor and Secondary Animal Products in the Eighteenth-Century Pimería Alta, Barnet Pavao-Zuckerman, American Antiquity (2011)

- Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500–1900, Andrew Sluyter, Yale University Press (2012).

- Range Limits: Semiferal Animal Husbandry in Spanish Colonial Arizona, Nicole M. Mathwich, American Antiquity (2022).